- Home

- Peggielene Bartels

King Peggy Page 12

King Peggy Read online

Page 12

The days were so exhausting that she slept like a log every night in the room with her five aunties, even though they always kept the light on so they could make it to the bathroom without stepping on another auntie stretched out on a sleeping mat.

One night Peggy woke up and saw a man sitting in the plastic chair next to her bed. She was surprised because usually visitors didn’t come between ten p.m. and four a.m., and whenever they did come, they cried “Kokoko!” to alert people to their approach.

His entrance hadn’t awakened any of Peggy’s relatives in the room either, which was strange because the bedroom door behind him was closed, and to do so you had to make a lot of ruckus, slamming it hard and jiggling the handle.

Her visitor was an elderly man with gray hair and a handsome face of strong, noble lines. Though he had the muscular arms of a fisherman, Peggy assumed that he was about eighty. He wore a multicolored cloth over his left shoulder. She wasn’t sure if she recognized him or not—she had met dozens of aunties and uncles and cousins in the past few days and couldn’t keep them straight. But she assumed he was one of her many relatives who had come to pay a late call.

He didn’t introduce himself, and Peggy was afraid to ask his name because perhaps she had already met him and didn’t remember, which he might find insulting. So she just pushed herself up to a sitting position and greeted him pleasantly as if she knew him.

He smiled at her. “Nana,” he said, “you must be strong if you want to live the full life of a king. There is nothing for you to be afraid of.”

It was an unusual comment for a visitor to start off with, but a wise one.

“I have many responsibilities,” Peggy replied. “Many worries, and not enough money by a long shot. I don’t know how I am going to do all this, take care of all these people.”

He chuckled. “You may not be aware of it yet, but there are so many people taking care of you spiritually, mentally, and physically.”

He must have meant the ancestors. “I know,” Peggy said. “But still it’s hard.”

He smiled at her and his dark eyes twinkled. “You will find the strength,” he said. “You are not alone in this. There is a reason the ancestors chose you as king. This was your destiny before you were born, you know. You will find the way to do great things for the people of Otuam.”

Peggy sighed and glanced over at Cousin Comfort, sound asleep beside her. It was strange that their conversation hadn’t awakened any of the other five women in the room. She looked back to respond, but the man was gone. The chair was empty, and the door, which made so much noise when closed, was still closed. It had been a dream, Peggy thought. The whole thing had been a dream. She eased back onto her pillow, staring at the chair where the man had been and thinking about what he had said, and finally fell asleep.

A few hours later, Peggy was aware of crowing roosters. She sat bolt upright and looked at the chair. It was still empty. Yes, that had been a dream, surely. Cousin Comfort stirred and turned around to face her.

“Good morning, Nana,” she said groggily.

“Comfort,” Peggy whispered, “last night I had a dream that an elderly man came in here and sat on that chair and told me things about my kingship. And all of a sudden he disappeared. That’s how I knew it was a dream.”

Cousin Comfort sat up and smiled. “Oh, no, Nana!” she said. “That wasn’t a dream. One of your ancestors visited you last night to advise you.”

“But if it wasn’t a dream, why didn’t anyone wake up when she heard him talking?” Peggy mused.

“That’s how it is with the ancestors,” Cousin Comfort explained. “When they visit you, they make sure everyone else is asleep and nobody wakes up. If some of the aunties recognized him as a long-dead relative, they would have started yelling and screaming, and then he couldn’t have delivered his message to you.”

Perhaps he had really been there, Peggy thought, staring at the empty chair, and she had spoken with an ancestor face-to-face. Funny how he had looked like a living person. He hadn’t been white or see-through or glowing, as you often hear in ghost stories, nor had there been anything at all frightening about him. Peggy had felt very calm when speaking to him and listening to his wise and encouraging remarks.

Peggy was far more afraid later in the day when she had another supernatural visitor. She was in the bedroom with the five other women when she heard a commotion in the hallway. Suddenly two wild-eyed men came in carrying what looked like a long wooden plank between them, resting on their left shoulders. A square object of some sort was on the center of the plank, but Peggy couldn’t tell exactly what it was because it was tightly wrapped in a white sheet.

The men’s attire was ordinary enough. They wore T-shirts, shorts, and flip-flops, but they looked very strange. They were sweating, dancing, and chanting, parading all around the bedroom with the plank and shrouded object. Cousin Comfort and Aunt Esi, who had been sitting on the bed with Peggy, stood up to welcome them, but the other three aunties threw themselves on the floor and cowered, their arms flung over their heads.

“What on earth…,” Peggy began, her mouth gaping.

“They are the fetish priests of the god Inkumsah,” Auntie Esi said knowingly. “These priests go into trances and the god makes them dance and speak in his voice. They tend his shrine in a secret cave on the beach.”

Then Peggy understood that the square object was a brass pan that contained a statue, called a fetish, inhabited by a spirit. Spirits, she knew, could glide invisibly across the earth like the wind, until they settled down and attached themselves to a body of water, a patch of forest, a hill, or a beach. Sometimes priests lived on the sacred site, pouring libations to the spirit and even letting it speak through their mouths when they went into trances. Such spirits were often called gods, though everyone knew there was only one Creator God, who had made everything in the universe, seen and unseen. Long ago some of these little gods had been coaxed out of their trees, caves, or lagoons to enter clay fetish images, which the priests kept in brass pans. In times of attack, the priests could run to safety carrying the fetish with them, whereas they couldn’t very well carry off a lagoon or a tree.

Inkumsah was, apparently, one of those spirits created at the dawn of time, older than the oldest ancestors, ancient beyond measure, and who knew how powerful. Perhaps he had been born in that cave on the beach, shaped by God along with the molten rock. Or maybe for millions of years he had wandered the earth disembodied, drifted to the cave, and there found repose as one of Otuam’s seventy-seven gods. Now this spirit was standing in front of her. Peggy shuddered.

“Welcome, Nana,” said the fetish priest carrying the front of the plank. His eyes darted right and left, and sweat poured down his face.

Auntie Esi nudged Peggy. “He’s speaking in the voice of the god Inkumsah,” she said. Peggy nodded, her eyes wide, her mouth open.

“Why, when you came here, did you not visit me?” the god cried, as the priest who was speaking jumped up and down. “I have known you for many years. Yet you come here for your enstoolment and neglect me.”

The god had known Peggy for many years? Really? She had never heard about this god before. How could she have visited him? But the words stuck in her throat. What were you supposed to say to a god dancing in your bedroom?

Peggy was relieved when Cousin Comfort cleared her throat and answered for her. “Nana is from the USA and doesn’t know the customs of Otuam,” she said. “If an error has been committed, it is not hers but ours for not advising her properly.”

“You must pay us something,” the god said, as the men jumped up and down with the plank between them.

“Pay?” Peggy asked, astonished. It seemed that everybody in Otuam wanted her money, even the cave god.

Cousin Comfort nudged her again. “Just one cedi. A symbolic act of devotion and respect.”

The men were dancing in circles again and shaking their heads, the sweat flying off them. Quickly Peggy grabbed her purse and t

ook out a coin. “Here,” she said.

“We are going now,” said Inkumsa, as his priest pocketed the coin in his shorts. “You must know that you have been chosen, and we will protect you.”

They danced out of the bedroom and out of the house, through the bush and down toward the beach. The aunties who had been cowering slowly raised their heads and looked around. Creakily, they stood up. Peggy just sat on the bed with her mouth hanging open, her pocketbook on her lap.

Most men think they are gods in the bedroom and their women pretend to agree. But that day Peggy had a real god in her bedroom, which is something most women could never say, and it scared the hell out of her.

9

The evening before Peggy’s enstoolment, she and her elders and aunties went to a wide concrete house with a large courtyard on Main Street for special ceremonies. The house belonged to a fifty-five-year-old retired engineer, Casely Kweku Mensah, known in Otuam by his royal title of Nana Tufuhiene or just plain Nana Tufu. He was tall and dignified, his gray hair cropped close. He had an intelligent, handsome face, wire-framed glasses, and from the neck up looked like a university professor. He wore a printed tan cloth, a dozen strands of beads around his neck, and several bead bracelets on each wrist.

Nana Tufu had a special role in the area as a mediator, which conferred on him the status of king. It traced back to one of his ancestors who had been known for great diplomatic skill. The ancestor had been drafted to mediate between the king of Otuam and the troublesome Magic Mirror clan, in a quarrel that had been going on for more than three centuries, back to the earliest years of Otuam’s existence.

Otuam had been founded by an ambitious young hunter, Peggy’s ancestor, Amuah Afenyi of the Ebiradze clan. Amuah Afenyi was the nephew of the king of a farming community, Ampraefu, which means “If you don’t weed, it grows.”

Amuah Afenyi tracked game wide and far. One day he came across an uninhabited place on the sea, where enormous schools of fish migrated, with rich soil good enough to grow yams. He obtained permission from his uncle, the king, to bring a portion of the clan’s burgeoning population to the area and start his own town, which he called Tantum, after a local god.

Once he and his people were well settled, and he had been enstooled as Nana Amuah Afenyi I, he received a visit from a man named Ewusi Kwansa and his wives, children, followers, and slaves. Ewusi Kwansa’s great wealth had come from a business opportunity he had seized in his youth: he had obtained a mirror from a Portuguese trader on the coast. In the interior of what is now Ghana, mirrors had never before been seen. Ewusi Kwansa had wrapped his mirror in a cloth and traveled from village to village, promising to show people what their souls looked like—for a fee.

Arriving in Tantum with his entourage, Ewusi Kwansa asked Amuah Afenyi for permission to stay a few days, a request that was granted by the hospitable host. But the Magic Mirror people refused to leave and dug their feet deeply into the ground, like stubborn tree roots that could never be pulled out. Soon they no longer regarded themselves as guests of the stool, but as rightful owners of the land.

After the deaths of Amuah Afenyi and Ewusi Kwansa, their heirs disputed ownership of Tantum, and the Ebiradze family cast out the people of Ewusi Kwansa. But they returned late one night, killing townsfolk as they slept and burning their houses. The Ebiradze rebuilt the town, vowing never to forget the ambush, though they couldn’t prevent the Magic Mirror people from eventually returning, claiming land and other rights, and always agitating for more.

More often than not, the peace-loving descendants of Amuah Afenyi I gave in to their claims rather than risking further violence, even ceding to them an acre of land they could legally call their own. But this act of generosity was a grievous mistake. Immediately the Magic Mirror people elected their own king with his own stool to rule over the acre and proclaimed themselves kings on par with the kings of Otuam. They even chose a royal family name that imitated that of the Ebiradze: they called themselves the Aboradze.

Peggy’s family looked at them as eternal, unwelcome houseguests who had to be suffered in silence. But in the 1950s some of them committed a heinous crime—Peggy could never determine exactly what they had done—and Nana Amuah Afenyi III changed the name of the town from Tantum to Otuam, which meant “He attacks me unawares.” It was a nonviolent slap in the face, aimed to ensure that no one would ever forget the sneakiness and greediness of the Magic Mirror people, who still lived among them.

The fractious relations between the two royal families became so bad that Nana Tufu’s family became the official mediators, raised to royal status to give their decrees greater force. Fortunately for Peggy, a few years earlier when the one-acre Magic Mirror king had died, his relatives got into a terrible fight over who should be the next king, with two branches of the family coming to blows. Neither one of the two contenders lived in Otuam or they might have stirred up trouble for her. With the family unable to choose a king, the one acre of the Aboradze remained kingless, which made the Ebiradze happy.

For several years now, Nana Tufu hadn’t been called upon to resolve any disputes between the two royal families. But he participated in local festivals, royal elections, enstoolments, and the funerals of kings in the region.

Nana Tufu himself hadn’t actually been enstooled because his family alternated kingship between its two main branches (a common practice in much of Africa), and he was sitting in for his cousin who wasn’t ready yet to leave his job and move to Otuam. Nana Tufu had taken the position four years earlier, and as each year went by with no sign of his cousin, he sank more deeply into the role and believed he would have it for life, as well he should, he often said, after so much effort.

Otuam’s royal mediator was almost always accompanied by his own tsiami, fifty-two-year-old Papa Adama. Short and wiry, he had a dark, skull-like face with widely spaced eyes, high cheekbones, a short triangular nose, and a long space between his nose and mouth. He was missing several teeth, yet instead of being unattractive it gave him a cute, friendly look, like a child who had lost his baby teeth and was waiting for adult ones to come in. Tonight he was wearing flip-flops and a pale green knee-length robe.

Like many in Otuam, Papa Adama was an illiterate fisherman. But if he couldn’t read or write, he could certainly speak with great authority. And now he cried out the official greetings to Peggy in a loud, ringing voice, perhaps the loudest, most passionate voice in all Ghana. He was like an ancient epic poet declaiming Homer, capturing the absolute attention of everyone within hearing distance. Papa Adama’s dramatic inflection put all the other tsiamis to shame.

African communication had always primarily been verbal rather than written. Little children were trained by their parents to speak clearly to their elders in family gatherings, prompted to find the right words, put them in a meaningful order, and above all, tell the truth and speak straight from the heart. Therefore most Africans were unfazed by speaking to huge crowds, even if they couldn’t read or write, while many Americans, according to a survey Peggy had read, were more afraid of public speaking than of death.

Peggy and her elders, along with Nana Tufu and his elders, gathered in his uneven concrete courtyard where the butcher slaughtered a goat as a sacrifice to the ancestors for Peggy’s enstoolment. The skin would be used to make a pouch or sandals, and the meat would be eaten. Then they went inside to Nana Tufu’s throne room, a wide chamber with a raised platform at the far end with the royal stool on it, where Peggy would be examined for her suitability as king. To be enstooled as a Ghanaian king, the candidate had to be in good health and show no signs of witchcraft, which were usually manifested in some kind of physical deformity. These included a twisted leg or limp, a bad eye, leprosy or any skin disease. He—or she—would also be disqualified if he were left-handed, or worst of all, had a sixth finger on either hand.

Nana Tufu and his council of elders carefully examined Peggy’s skin, looked closely at her eyes, inspected her hands, and made her walk up and down. She

was glad for her aunties’ royal training because now she walked slowly, with great dignity. After consulting with one another in a corner, they agreed that Peggy was a fit specimen for kingship.

On their way out of Nana Tufu’s palace, Tsiami took Peggy aside and remarked, “When I was consecrating your sacred stool, it told me it didn’t like schnapps and only wanted to drink Coke.”

Ghanaian women usually didn’t drink hard liquor, and Peggy found it fascinating that her stool shared this female abhorrence of strong drink. It was clearly imbued with a female spirit.

The next morning, Peggy and the aunties were up at four a.m. They bathed in their buckets, dressed, and breakfasted. Peggy was given a special anti-urination breakfast of yams, boiled and mashed, with palm oil and hard-boiled eggs mixed in. Her aunties assured her that this dish would take away all urge to pee for about eighteen hours. It would be terribly undignified if the new king had to instruct her bearers to put down the palanquin in which she would be carried so she could run off to the nearest toilet.

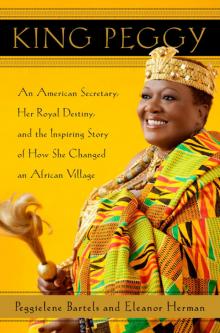

Peggy wore her late uncle’s red, green, black, and gold kente cloth slung over one shoulder. The red stood for sacrificial rites and death, the green for spiritual renewal, the gold for royalty and glory, and the black for the intense spiritual energy of the dead. But she wore something under her kente that most kings didn’t bother with—a long-line strapless bra.

Peggy also wore Uncle Joseph’s royal sandals, leather flip-flops with wide round toes and heels. The V-shaped strap was made of woven strips of brightly colored leather and decorated at the top with a multicolored pom-pom.

King Peggy

King Peggy