- Home

- Peggielene Bartels

King Peggy Page 3

King Peggy Read online

Page 3

Otuam’s farmers worked all day in the fields, cultivating pineapples, yams, and papayas, planting and weeding, fertilizing and harvesting. But it was the fish that brought the town a measure of prosperity and its immunity from famine whether the rains came or not. Six days a week the fishermen hauled in heavy nets of fish—mackerel, herring, red snapper, tilapia, and salmon—from hundreds of feet out at sea, sometimes pulling for eight hours straight, while their wives cleaned the fish and sold it on Main Street from large silver buckets on their heads.

Whether the wives of fishermen or farmers or owners of their own little Main Street shops, Otuam’s women spent some time every day outside. Peggy could picture them sweeping the dirt with palm fronds, feeding chickens, smoking fish in large clay ovens, washing clothes in vats, and pounding cassava root into a white paste called fufu, which was something like mashed potatoes.

The town hadn’t changed much over the decades Peggy had visited it and seemed to be a world unto itself. Even its dialect of Fante was heavy, archaic, using riddles and proverbs the way people had spoken centuries earlier. The Otuam dialect was linguistic proof of the town’s scant interaction with the wider world. It seemed that few people ever left Otuam, and even fewer moved there from elsewhere.

Otuam’s slow pace gave it one great advantage over more modernized towns: its original gods and goddesses hadn’t been chased away by traffic jams, blaring horns, and the hectic lifestyle the spirits despised. Peggy recalled Tsiami telling her once that Otuam had seventy-seven gods and goddesses who lived on the beaches and in the fields and woods, while their counterparts in the cities had long ago fled the noise and bustle. Otuam’s spirits, Tsiami had said, were exceptionally strong and intervened frequently in the lives of the town’s inhabitants, rewarding good people and punishing evil ones.

But there wasn’t much evil to punish: no murders, rapes, armed robbery, or arson that she had ever heard of. Peggy tried to remember something her mother had told her years ago, something unpleasant about the town. Yes, that was it. Some of Otuam’s men got drunk and beat their wives, and that was certainly a mark against the place. If she decided to accept the crown, her first order of business would be to put an end to that. But overall, most people were kind and friendly, often taking the time to chat with a friend or visit a neighbor, or sit quietly under a shade tree and watch the shafts of sunlight slanting down through green branches.

Peggy loved Ghana because its twenty-four million inhabitants were known as the friendliest, most peaceful people in Africa and probably in the whole world. They didn’t want to rule over anybody, or steal other nations’ resources. They just wanted to work hard, stay healthy, and enjoy their friends and families.

This was even true in centuries past. Peggy’s Fante tribe had, for the most part, interacted harmoniously with the European traders who built fortresses and towns on the coast. The Portuguese first arrived in the late fifteenth century, and within a few decades the Dutch, British, and Danes joined them to trade in slaves, ivory, and gold, developing the local economy and bringing in what the native people considered to be luxury goods. By 1874 Great Britain had either conquered or purchased the other nations’ forts and made Ghana, then called the Gold Coast, into a colony.

English became the official language, though every region had a tribal language, which in most of southern Ghana was Fante. Across the colony, school instruction was in English; businesses and streets had English names. Many Ghanaians in the cities even took English surnames, as Peggy’s father’s family had, and gave their children English first names, often from the Bible.

The Fantes’ acceptance of colonization was fueled by their fear of their aggressive neighbors to the north. The powerful Ashanti tribe was building an empire of its own and fielded half a million soldiers by the mid-nineteenth century. The peace-loving Fantes realized they, too, would be conquered by the Ashantis if the British didn’t protect them, though by 1902 even the Ashantis had been forced to submit to British rule.

The Fantes embodied the nonviolence, hospitality, and friendliness of modern Ghana, and Peggy supposed that the people of Otuam were the most peaceful of the peaceful. The symbol of Otuam, the figures carved on top of the chief priest’s speaking staff, Peggy remembered, were a gun, a snail, and a turtle. During her last visit there, she had asked Tsiami what those symbols represented. He had told her that they came from an old Ghanaian proverb that said a hunter in the bush wouldn’t bother himself with a turtle or snail, peaceful creatures that stayed low and quiet on the ground. The hunter would shoot a lion or rhino, powerful, aggressive creatures. The people of Otuam felt no shame in seeing themselves as the snail and the turtle. In fact, they felt it was a clear indication of their intelligence; snails and turtles would never get shot. Yes, it seemed to Peggy that it would be fairly easy to rule over the peaceful people of Otuam.

If there was one thing holding Peggy back from accepting the crown immediately, it was Otuam’s poverty. The town had no gold mines or factories like other parts of Ghana. It couldn’t boast any of the large Ghanaian cocoa plantations owned by Nestlé or Cadbury where local residents earned good money by harvesting the basic ingredient of chocolate to make world-famous candy bars. Otuam had its fish, mostly, which was enough to keep the people fed and healthy, and that was about it. No one starved, but many lived hand to mouth.

Did the king collect any taxes or fees? She didn’t know. All the land in a town or village belonged to its king, she knew, as well as to the dead and the unborn. But the king had the right to decide who would live on it. Did he do so for a price? Even if there was some income in Otuam, it probably wouldn’t be sufficient for the king’s many expenses. During her last visit to Uncle Joseph in the royal palace, Peggy remembered, a chunk of plaster had fallen from the ceiling and no one had seemed surprised.

The derelict condition of the palace had been the root of family dissension for many years. After the death of Uncle Rockson, who had built it from scratch and lovingly maintained it, his successor never lifted a finger. The rainy season in coastal Ghana did a lot of damage to roofs and walls, and when the heaviest rains ended in late August, most families brought out ladders and cement to patch things up. But not Uncle Joseph. When a big hole opened in the ceiling over the king’s bed, he put a bucket in the middle and lay on one side of it, and his wife on the other.

Uncle Rockson’s younger brother, Uncle James, was horrified. He bought cement with his own money to patch up the walls and brought the bags to Otuam as a gift to the king, and he even offered to have his own workmen do the repairs. But Uncle Joseph seemed offended by the offer. The bags sat in the courtyard, and during the next rainy season, they got wet and turned to cement blocks.

Peggy suddenly remembered a day long ago when she was on break from catering school in London and visited her mother. “I’ll be going to Otuam,” Mother said. “There’s trouble afoot between Uncle Joseph and Uncle James about the palace. So the family is meeting to try to resolve the dispute. Do you want to come? ”

Peggy had yawned. What did she care about falling-down palaces and the arguments of old men? “I’ll stay here,” she said.

And now, ironically, if she accepted the kingship, the falling-down palace and the arguments of old men would land squarely in her own lap. For if she became king, she would have to arrange Uncle Joseph’s funeral, which she couldn’t begin to do until she had entirely refurbished the palace.

A magnificent royal funeral, held in an impressive locale, reflected glory not only on the deceased, but on his successor and his people. Such events typically lasted three days and were enormously expensive. Hundreds of the late king’s subjects would show up, along with neighboring kings and their elders and relatives, and they all drank whiskey and ate meat from freshly slaughtered cows. The deceased would be interred in a tomb within the palace.

If, in her haste to put Uncle Joseph to rest, she gave him a poor funeral in the crummy courtyard of a decrepit palace and entombed him behi

nd a tottering, leaky wall, his spirit might haunt her for the rest of her life. Then again, if she left him in the fridge in Accra for a long time, that would make him mad, too. He would be wandering in limbo, that gray world in between life and death, not fully welcomed by the ancestors until after his funeral. Peggy winced at the prospect. Either way, if she became king, it looked like she would be haunted.

Peggy wondered if she could count on the late king’s children to help her with these expenses. There were five of them, two boys who had moved to Houston and become U.S. citizens, and three girls who lived in Accra.

She strained to remember what Mother had told her: something about the children’s anger at their father for leaving their mother and not supporting them. He had gone from woman to woman, finally settling down with an Otuam fishmonger in the palace, ignoring his children’s requests for financial help. So the children went without, just as the palace now did.

Far more serious than the falling-down palace was the water situation in Otuam. During her 1995 visit there had been no running water, and she doubted they had gotten any since then. The British colonial government had put in pipes in 1950, and many houses had a toilet, sink, and shower. But the pipes had gone dry in 1977, and no one knew why. Was it a massive rupture underground? The faulty new pumping station thirty miles away? The Ghanaian government never investigated because it didn’t have the money to fix the pipes whatever the cause. Thousands of villages needed water, and the funds simply weren’t available.

Since then the town had dug a couple of boreholes on its outskirts, pumps where you would set your bucket under the faucet on one side and jump up and down on the long handle on the other side to make water come out. Most families relegated their children to water duty, and kids as young as five walked every day for miles before school to carry heavy buckets on their heads.

As an American she couldn’t let her people live without running water. It was unthinkable. Yet how would she fix whatever was wrong with the pipes? How much would it cost? Who would she ask to look into it?

The truth was, if she became king, seven thousand people in Otuam would be counting on her to improve their lives. It was a huge responsibility. And daunting as the job was, she couldn’t devote herself to it full-time, at least not yet. Right now she had a job, a condo, a life in Washington. She would have to rule the kingdom from afar, returning perhaps once a year for as many days as her boss permitted, and move to Otuam once she retired. Would the elders be okay with that?

And then there was the question of whether she could do the job at all. Peggy had never been trained for an executive position. She had never run a company, sat on the city council, or even managed a store or restaurant. For twenty-nine years, she had carried out the instructions of others who gave her documents to type, people to call, and coffee trays to set up. For decades, she had followed the vision of her bosses, not her own.

Could a good secretary be a good king? She turned the dilemma around in her head, examining it from different angles. As a secretary, she had to think on her feet, understand people’s needs, and find solutions to a wide variety of problems, whether technical, interpersonal, or financial. She had worked diligently to acquire new administrative skills, which, she believed, could be quite helpful in running a small kingdom.

In some cases, she had advised her bosses on improving efficiency, troubleshooting problems they were unaware of. Surely that ability would help her rule in Otuam. And after doing her boss’s expense accounts for years, she could organize the town’s financial matters.

As king, she would have to deal with a variety of conflicting personalities—her elders, her subjects, government officials, and potential investors. As a secretary, she had dealt with embassy staff from all of Ghana’s tribes—the Fantes in the south, fun loving and friendly; the Ashantis in the middle, shrewd businessmen; the Ewes in the east, extremely conservative and trustworthy; and the “northerners” in the arid region, a complex group of Muslim tribes feared for their generations-long blood feuds. She also dealt with pencil-pushing U.S. government bureaucrats, flamboyant African heads of state, and members of the general public, who ranged from the polite to the insane.

Yes, being a good secretary required its own kind of leadership and vision, as well as flexibility and resourcefulness. The one blip in her personnel file—her prickly, autocratic spirit—could be seen as proper in a king. Perhaps those very qualities that made some consider her to be arrogant or aloof might help her to be a truly good ruler.

As king she would have to work closely with her council of elders. Technically, the royal council was advisory in nature, counseling the king on all matters that required his attention, from settling disputes among townsfolk to organizing royal ceremonies. However, it was very bad form for a king not to consider the elders’ advice and stubbornly go his own way. Arguments were permitted between a king and his council, but in the end they were expected to reach a consensus.

She pictured herself meeting with Otuam’s council of elders, men in their seventies and eighties, set in their ways and used to telling women what to do. And not only was it awkward that she was a woman. There was another consideration: Peggy was significantly younger than her elders. Even if she were a man, they would have a hard time hearing criticism from a younger person. Age seniority was so important in Ghana that someone might say, “Hush, you youngster! I am older than you are! Have respect for your elders!” even if he was older by one day. Twenty to thirty years younger than her elders, Peggy would be considered almost a child in their eyes. How on earth was she going to rule over a council of traditional old men? An amicable consensus on important issues would be impossible if they tried to boss her around, she knew, because a king shouldn’t meekly follow orders from anyone, except God.

She sat there and thought and thought about it until the sun came up and it was time to pour libations. For centuries, perhaps millennia, African tribes had poured libations to their ancestors and worshipped the divine in every living thing, even in objects. Souls, they believed, were not limited to human bodies, for God was all-powerful, and everything in the world he made must therefore possess an immortal spark. Spirits could inhabit bodies, clearly, for such was the case with human beings. Or they could inhabit plants, rocks, or even man-made objects. Peggy often spoke to the female spirit of her car, a 1992 Honda, begging her to keep going for just a little while longer.

Like many Ghanaians, Peggy mixed Christianity with her ancestral religion, animism, into something that you might call Christianimism. To the dismay of the missionaries who brought Christianity to Ghana, many of those who had jubilantly converted also continued their ancestral traditions. They saw Jesus, born of a virgin and resurrected from death, as one of God’s countless miracles, along with thirsty ancestors and objects that could think.

There were, of course, some Christians in the big cities who scoffed at the pouring of libations as a tragic waste of good liquor and some animists in the bush who ridiculed Christianity as a tool used by white men to colonize black ones. Peggy was raised to see truth and beauty in both traditions and combined them flawlessly. While pouring her morning libations to the ancestors, she also asked Jesus for guidance and wisdom. Afterward, she read the Psalms and the Gospels.

Today she prayed with particular fervor. “Mother,” she said, tears sliding down her cheeks. “Wherever you are, I know God and Jesus are there. Please ask God and Jesus to help me because I have a big decision to make, and I honestly don’t know what to do.” She poured the gin, and it pooled on the carpet.

What would Mother advise Peggy to do now? Her last words on this earth, before Peggy could get to Ghana to see her, had been about her favorite child: “Tell my daughter I have been climbing the hill a long time, and now I am on the top. I am very tired, so I am going. But tell Peggy that she is very special, and she must stand up loud and clear for what she knows is right. She must be strong, but always remain humble.” And then she was gone, and the world was e

mpty.

Peggy prayed to Uncle Joseph for the first time ever, now that she knew he was in the village for good. “You wanted me to be king after you,” she said. “And I have been chosen. Now I need your help in making this decision.” She poured some more gin.

Then she prayed to all her ancestors going back in time. “Please help me,” she said. “Show me the way.” And she poured the gin a third time. Now there was a big puddle on the carpet, which slowly sank in and darkened the stain. One of these days when she could afford it she would have to get some new carpet. Maybe in a darker color.

And then it was time to get ready for work. In the bathroom she studied her face in the mirror. “Hello, king,” she said out loud. “King Peggy,” she added, and burst out laughing.

Was this the face of a king? She ran her fingers over the smooth golden brown skin. Other than the folds that ran from her nose to her mouth, there were no lines on her face, though that was likely because of her weight gain. If she lost the weight, would her skin sag like that of so many women her age? Would she look like a bulldog? She didn’t know. Women, she thought, were relegated in middle age either to a wide rear end or a crinkled dog face. Perhaps it was better to have the wide rear end, all things considered.

The eyes looking back at her were large, dark, widely set, and expressive. Her nose turned up, like that of a child. Her lips were full, her teeth white and even. She turned her head from side to side, looking at the angles. It was a strong face, a noble face, perhaps the face of a king. She didn’t have much in the way of eyebrows, though. Maybe if she became king she should pencil them in to look tougher. No, she liked them the way they were.

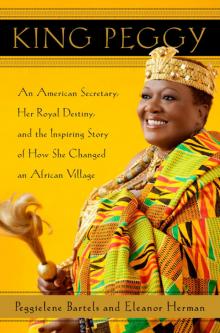

King Peggy

King Peggy